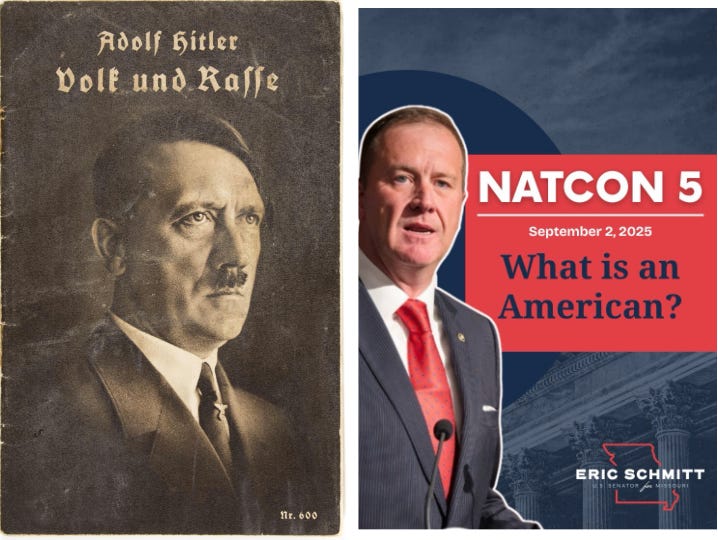

NatCon or Nuremberg?

Missouri Senator Eric Schmitt (I hope not a relation) gave a doozy of a speech at the 5th National Conservative Conference this week (aka NatCon5, which sounds, appropriately, like an event for exterminators), wherein he resurrected some truly choice early 20th century tropes about race and the capacity to self-govern. In his telling, not everybody is cut out for freedom and democracy, especially, it seems, those whose skin is darker than his. But let me let this charmer speak for himself:

“We Americans are the sons and daughters of the Christian pilgrims that poured out from Europe’s shores to baptize a new world in their ancient faith. Our ancestors were driven here by destiny, possessed by urgent and fiery conviction, by burning belief, devoted to their cause and their God.

If you imposed a carbon copy of the U.S. Constitution on Kazakhstan tomorrow, Kazakhstan wouldn’t magically become America. Because Kazakhstan isn’t filled with Americans. It’s filled with Kazakhstanis!

What makes America exceptional isn’t just that we committed ourselves to the principles of self-government. It’s that we, as a people, were actually capable of living them.”

My apologies to any Kazakhstanis who may read this, but it’s a deplorable truth that the United States is presently run by cruel, stupid, bigoted… Americans. That’s, however, not the point I wanted to make here (American politicians like Schmitt—again, if I’m related to his monkey ass, I apologize—are doing a brilliant job making that clear all on their own). What I want to focus on is this pernicious idea that some people are more fit to self-govern than others, that white Americans are somehow genetically endowed to be superior in this capacity. It’s an idea with a long and ugly pedigree—as a matter of fact, Schmitt (again, fuck me that he’s using my last name) is cribbing straight from the scientific racism that justified slavery in American, as well as the extermination of native people on both the continent, and in U.S. imperial possessions. It’s really crazy, honestly, how much this guy sounds like the bloviating early 20th century senators who didn’t want New Mexico admitted to the union because they claimed there weren’t enough white people there to form a credible state government; or argue that Filipinos were too backwards for it to matter whether or not they consented to American rule (btw: they didn’t, but the U.S. ruled them as a colony for 50 years, anyway).

As it happens, I’m currently working on a book project that deals in part with these arguments about race and self-government in American history. In particular, I focus on how American Indian policy, particularly as it related to Cherokee self-government, and early U.S. imperial policy in the Philippines, drew from the same racist ideas about how biological inheritance determined the capacity for self-rule. I’ve posted a chapter discussing this below. And please, be warned, its a rough draft, so I’m sure it needs a copy-edit. I should also say that the book is an academic work, thus it’s written in an academic style, and follows academic conventions. I’ve taken out the footnotes, but the superscript numbers remain in the text (formatting is the bane of my existence), so I ask you to indulge that annoyance.

Also, I’d love any feedback or questions. They help tremendously in improving the overall book project.

The American Imperial Archipelago: Race and The Capacity to Govern in Indian Territory and the Philippines

As Eric T. Love has argued, racism exerted a checking power on American imperial ambitions over the course of the nineteenth-century.688 The Philippines, for example, could never become a part of the United States because of the perceived insoluble racial difference between the two countries. This same challenge presented itself to the federal government with the Cherokee nation and the rest of the Five Nations. As polities primarily of aboriginal “racial” stock, they could not become a U.S. territory proper, much less a U.S. state. When, however, it was deemed that the Indian “blood” had been sufficiently diluted among the Five Nations—when, ironically, the deleterious influence of white blood became the target of Congressional remedy—only then was the incorporation of Indian Territory into the United States (and the granting of inhabitants citizenship) considered.

The “Indian” population of Indian Territory, for their part, continued to work to maintain at least a marginally distinct political identity. In 1905, representatives from the Five Nations convened to draft a constitution for the proposed Indian state of Sequoyah. At the time of the convention, a bill to admit Indian Territory and the territory of Oklahoma into the Union as a single state was pending in Congress. In a memorial to Congress that included the Sequoyah constitution, the Five Nations convention made the case that they possessed “the natural right to be recognized as a distinct and self-governing people, because of the peculiar character of our populations, and as practically all of the land in Indian Territory is owned by the Indian people.”689 They also expressed the fear that if joined to the territory of Oklahoma, its inhabitants, whose only experience with Indians had been with the “wild tribes…would naturally have sentiments in regard to Indians that would make them unfriendly and inconsiderate toward the Indians of Indian Territory.” Moreover, the memorial stated that the United States had bound itself to admit the Indian Territory as an individual state by the various treaties with the five nations (the principal clause in each being the U.S. promise to not include any of the Nations with the boundaries of another U.S. state or territory); the conditions under which the United States acquired the territory in question with the Louisiana Purchases which provided that all the territory therein would eventually be admitted to statehood; and by stipulation of the Curtis Act itself, which stated that allotment of the nation’s lands was done with intention of future admission to the Union.690

The appeal to natural right here is an interesting one, particularly in the context of the Cherokee nation having argued for their sovereignty in U.S. courts over the course of the nineteenth-century on more positivistic grounds like treaty rights and de facto attributes of formal sovereignty like demonstrated self-rule. Natural rights in many ways had been the bane of the Cherokee, as their residual influence in an emergent nineteenth-century Euro-American positive jurisprudence had condensed into the principle of “occupancy” and the corporate-racial category of “Indian tribe,” both of which had operated to undermine the Cherokee nation’s “international” political standing. The appeal for separate statehood, however, was made in the context of the United States having already taken draconian (and self-interested) remedial action against the governments of the Five Nations based on their allegedly demonstrated inability to effectively govern. The fact that this seemingly positivistic judgment was itself based in jurisprudential reasoning about the inherent nature of aboriginal title tightened the second ligature of the double-bind.

The conceptual legalistic snares the Cherokee were tangled in notwithstanding, Congress was not in the end sympathetic to their argument for statehood. Bills were introduced with that goal in both Houses in 1906, but neither received a hearing. With the encouragement of President Roosevelt, a bill for joint statehood passed Congress in the summer of 1906, and the efforts of the Five Nations to maintain a measure of political independence were brought to an end. The House Committee on the Territories made clear the reasoning behind single statehood in January of 1906, when it observed that since the 1900 census, the population of Indian Territory had increased with “amazing rapidity” (the safe assumption is that increase was comprised of white Americans), and that the boundary line separating Oklahoma and Indians territories was an artifact from a time when Five Nations still governed. After passage of the Curtis Act, that border was “arbitrary and irregular”; and, moreover, its abolishment was prefigured in the 1900 Oklahoma Organic Act itself, which stated that the Indian Territory would be joined to Oklahoma “whenever the Indian Nation[s] signify to the President of the United States in a legal manner [their] assent that such land should become part of Territory of Oklahoma.” Apparently it didn’t trouble the Committee that no such assent had been given. Regardless, Congress no longer perceived the Indian Territory as the exclusive purview of the “Five Tribes.” The increase in population was sufficient to convince legislators that the racial profile of the land had tipped toward white America, thus the Oklahoma and Indian territories could be joined and admitted to the Union without creating an ethnic disturbance in the American republic.691

Race and the “capacity” for self-government were virtually inextricable categories for late nineteenth and early twentieth century American legislators. Dispatches to Congressional commissions sent to investigate the “conditions in Indian Territory” alleged time and time again the lawlessness and injustice of the Five Nations’ governing institutions. The failure of these institutions had purportedly resulted in the exploitation of the docile and crude “full blood Indian” by a cadre of mercenary “half-breeds” (and, in some cases, equally opportunistic adopted whites). It’s interesting to note, however, that the introduction of white blood into these nations—into their societies and into their political institutions—did not, according to American lawmakers, in and of itself ameliorate their “deplorable condition.” As Bethany Berger has noted, American Indians—at least in part of the nineteenth century—were racialized more readily in the collective than individually. This is precisely why breaking up communal land tenure into private holdings became the overriding nineteenth and early twentieth century answer to the “Indian question.” In this context, adoption of white Americans into aboriginal political society could not instigate “reform” because the social and political institutions these whites were adopted into were by their nature deficient, if not wholly corrupt. In an 1894 report from the Select Committee on the Five Civilized Tribes (which visited Indian Territory a year before the Dawes Commission, and of which Senators Henry Teller and Orville Platt were members) a grim assessment of the Cherokee and the nations in Indian Territory was guided by this presumption:

It is apparent to all who are conversant with the present condition in Indian Territory that their system of government cannot continue. It is not only non-American, but it is radically wrong, and a change is imperatively demanded in the interest of Indian and whites alike, and such a change can be no longer delayed. The situation grows worse and will continue to grow worse. There can be no modification of the system. It cannot be reformed. It must be abandoned and a better one substituted.692

The following year, the Dawes Commission expressed moral outrage at the fact that the Five Nations government exercised virtually autocratic control over the ever-increasing white population in Indian Territory. This population had “had no foothold in the soil in voice in the government”; and thus, Commission maintained, were subject to a system of rule without their consent.693

As Sarah Cleveland has observed, “consent” and the “capacity to govern” were salient features of legislative and Supreme Court discourse in both the annexation of Indian Territory and America’s contemporaneous pursuit of extraterritorial imperialism. In both cases, race converged with the presumed ability to effectively manage civil governments (and thus, exercise sovereignty). On the one hand, non-white polities were perceived to lack the capacity for “civilized” self-government (at least if left to accomplish the latter without intervention from the United States); and on the other was the complimentary American assumption that because these polities were incapable of self-government, subjugation to U.S. rule did not require their consent. The racial aspect of this this is starkly portrayed in the Dawes Commission’s criticism of the “misrule” in Indian Territory where the white population was subjected to a government in which they had no say, simultaneous with its recommendation that the Five Nations governments be overthrown, regardless of the Indian population’s consent.694

This cognitive dissonance surrounding consent and race and self-government was on consistent display in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as the United States consolidated its territorial empire in North America and made its first substantial foray into “extraterritorial” colonialism. Legislators like Senator Albert Berveridge (Indiana) were exemplary of these prejudices; and as such were instrumental in setting the parameters of twentieth century U.S. imperialism.

Beveridge was the chairman of a 1903 Territorial Committee that considered the admission of Oklahoma and Indian territories as a single state. The same committee also was also set with the task of evaluating New Mexico’s bid for admission. He supported the Oklahoma single statehood, and yet stridently opposed New Mexico’s promotion from territory to state. In both cases, the racial demography of the states—associated explicitly with their ability to govern—determined his opinion.695

Beveridge’s primary objection to the New Mexican admission was his belief that the relative paucity of white settlement in the territory made its inhabitants unfit for self-government. In an 1898 speech entitled “The March of the Flag,” Beveridge referred to the non-white population of New Mexico (Nuevomexican peasants and Indians) as “savage and alien,” and their predominance over whites in the territory made the Territory of New Mexico “hapless and incapable of self- government.”696 He endorsed Oklahoma and Indian territories’ admission as a signal state based on the gaining predominance of white Americans in the region. In a 1903 debate on Oklahoma statehood, he said “out of this great population, only a small fraction are Indians, and therefore the objection that we are proposing to admit a great horde of Indians to citizenship—uncivilized people as I have heard them called around the Senate Chamber—is answered.” 697

Beveridge’s ideas about who could legitimately govern, and who deserved to be a fully-dressed member of the United States were not bound to the North American continent. His reputation in the Senate and in the American public was that of a brazenly unapologetic imperialist. In 1900 debate on, as another Senator on the floor put it, “the constitutions, and other documents of that kind in which the Philippine Islanders,” had drafted, Beveridge went on at length explaining not only the United States’ right to hold and govern the Philippines, but its moral obligation to do so. He had been to the Philippines in 1899 soon after being elected to his first term as a Senator. And just as his ideas of racial “capacity” and governance informed his work as the Chair of the territorial committee for the admission of Oklahoma and New Mexico as states, so too did it shape his image of the Philippines. Upon his return, he subjected the Senate to a lengthy airing of his views:

[Filipinos] are a barbarous race, modified by three centuries of contact with a decadent race. The Filipino is the South Sea Malay, put through three hundred years of superstition in religion, dishonesty in dealing, disorder in habits of industry, and cruelty, caprice and corruption in government. It is barely possible that 1,000 men in all the archipelago are capable of self government in the Anglo-Saxon sense.698

In the same speech, he went on to employ some truly pyrotechnic sophistry to argue that “the consent of the governed” actually implied, in some cases, governing polities without their consent. Government by consent, Beveridge told his fellow senators, was just one means to the end of “life, liberty and happiness,” which, taken together, was the true object of the Declaration of Independence. Consent, however, required and understanding of what was being consented to; and the Filipinos—by Beveridge’s own “investigation—were not capable understanding the form of government that would lead them to “life, liberty, and happiness,” thus it was America’s duty to govern them minus their consent.699

The self-serving nature of this reasoning aside, Beveridge was not hard pressed to point to other examples of the United States governing subject peoples with no thought to whether or not they desired to be governed: American Indians had never invited the United States to rule them; and yet “the sons of the makers of the Declaration have been governing [them] not by theory, but by practice, after the fashion of our governing race, now in one form, now by another[.]” It was the prerogative of the white “governing race” that formed the most “elemental” aspect of his argument. Although he saw no constitutional obstacle to American empire in general, and none to governing that empire “as we please,” neither of these, had they existed, would have shaken his zealous conviction in the fate of the “English-speaking and Teutonic peoples” to be “master organizers of the world where chaos reigns.” And of that race, he continued, “[God] has marked the American people as His chosen nation to finally lead in the regeneration of the world.” Ultimately, Beveridge’s justification for American empire was summed up in one terse declarative: “It is racial.”700

Beveridge, while maybe the most rhetorically florid, was far from the only senator701 who believed that consent to rule was a relative concept. Orville Platt, Henry Teller—both of whom, it should be remembered, was a central voice in the push to unilaterally overturn the Five Nations governments—Joseph Foraker, Henry Cabot Lodge and many others found it beneath Congress’s station to seek the consent to govern from “savages” ranging over a chain of Islands in the remote Pacific. But those in the imperialist (or, as they often phrased it, expansionist) camp faced staunch opposition from the vocal anti-imperialists legislators, George Vest, George Frisbee Hoar, in the senate, and contingent of representatives led by William Jennings Bryan in the House.

In 1898, Vest introduced a resolution in the Senate to opposes Untied States’ acquisition of extraterritorial possessions as was stipulated in the Treaty of Paris which ended the officially closed the Spanish-American war. The resolution insisted that that the constitution did not permit the United State to acquire and hold colonies against their will. This staunch opposition to U.S. extraterritorial empire seems at first to contradict Vest’s active promotion of the territorial incorporation of the Five Nations throughout the post-bellum period, which culminated with his resolution to appoint the Dawes Commission in 1892. In his speech to the Senate in support of that resolution, he said that due to substantial white population that had settled in Indian Territory by the last decade of the nineteenth century, Congress could no longer countenance the Indian governments. Ten years earlier, in a speech in support of extending federal jurisdiction over the Five Nations, he professed to never having understood Marshall’s characterization of the Cherokee (and, by extension, Indian tribes in general), as “independent dependencies”—beyond his bafflement at this illogical construction, he could not see how any “independence” inhered to polities to whose land the United States asserted superior title.702

But for Vest holding extraterritorial colonies was another matter entirely—at least if those colonies were not intended as eventual candidates for statehood. And when it came to defending that position in the face of undeniable U.S. colonization of Indian polities in North America, Vest insisted that Indians were the constitutionally permitted exception to the rule. Interestingly, in defending this point he cited the same Supreme Court decision he’d earlier professed not to comprehend. Cherokee Nation v Georgia, he argued, settled the matter of the U.S.-Indian relations by adjudicating it “utterly anomalous”; and by that anomaly, the fact that Congress “exercised by legislation the power of control” over Indian polities did not flout elemental principles of American government. To take possession, however, of “vast tracts of land inhabited by barbarians,” outside of the continental territory the United States, with no intention of eventual incorporation, would amount to “a fantastic and wicked attempt to revolutionize American government.” It would also, according to an article Vest wrote for the North American Review in 1899, mean “social and political deterioration, and the destruction of free institutions.” Why? Because the islands’ “savage natives” were inclined to “’run amok” and perpetrate “indiscriminate and murderous attack upon everybody within reach until physical exhaustion terminates the recreation.” Vest’s hyperbolic description of the lawlessness in the Philippines mapped neatly over his harangue against the failure of the Five Nations governments in Indian territory a mere five years earlier: “crime is rampant, corruption is rife…go into the Indian Territory to-night, ride to any house, make the usual hail of the West to the inmates, and you will have not response; every man is on guard[.]”703

Vest clearly believed that both Indian Territory and the Philippines were bereft of American civilization; and yet for structurally different reasons. In Indian Territory, a racially corrupt government (either by dint of too much Indian blood or to little) exercised autocratic control over a white population that had virtually no consistent access to courts of justice. The answer, then, was for Congress to abolish the Indian governments and manage the inevitable moment when “our race, the aggressive and dominant race of all the ages, will force itself into this Territory,” in order to prevent the “primitive,” full-blood Indians from being left landless and impoverished. In the Philippines, on the other hand, as of the time of the Treaty of Paris, the islands were teeming with some “3,000,000,000 savages” and somewhere near “3,000 whites,” (and those concentrated in the environs of Manila). Vest did not think these demographics likely to shift, as “no intelligent American can see why we should leave the safe and sure policy of a century for this dangerous experiment”—that safe and sure policy being territorial over blue water empire.704

In this light the Vest’s adamant belief in the United States’ right annex Indian Territory no longer appears so markedly at odds with his opposition to U.S. extraterritorial imperialism. Looking beyond the basic constitutional objection to annexation of the Philippines, the underlying racial animus is evident. Vest and his anti-imperialist colleagues did not object to the United States acquiring territory in all cases, but only in those that the territory in question would have to be governed without the intention of inclusion in the Union. And race was the overriding criterion for that inclusion. Vest’s concern was less about governing without Filipino consent than with the existential implications for the United States of governing the Filipinos as U.S. citizens. As Eric T. Love has observed, “the citizenship provision of the constitution put race at the center of this debate for Vest and turned the senator, and many others no doubt, against empire.”705

Vest’s persistent agitation to annex Indian Territory, on the other hand, was based on his belief that the aboriginal governments had a pernicious affect on the white men and women (be they intruders or immigrants) over which they ruled. And by his logic, throwing U.S. jurisdiction over the Cherokee and the other nations in Indian Territory was completely within the constitutional ambit of Congress, due the alleged sui generis nature of U.S.-Indian relations, and “menace” Indian Territory posed to U.S civilization. Moreover—and maybe more importantly—by the last decade of the nineteenth-century, Vest saw an Indian Territory the demographics of which were tipping toward white American, a trend in population flow that showed no signs of tapering.

Legal scholar Christina Duffy Burnett has done revisionist work on the jurisprudential ideology that underwrote U.S. annexation of the Philippines, claiming that when the Supreme Court considered the constitutional bounds of U.S.-Philippine colonial relations, validating the exercise of plenary power over dependencies was less a concern for the justices than establishing a legal framework within which the United States could eventually “de-annex” the islands. With Indian Territory, Congress pursued a prototypical version of this annexation/de-annextion strategy in order to both liquidate a scabrous relationship with a colonial imperil possession, and to further dilute the Indian population when the territory would eventually become a state. From the passage of the Curtis Act in 1898 to the passage of the Oklahoma Organic Act of 1906, Indian Territory was effectively an American colony. And just like the Philippines, that colony, in and of itself, was not one considered admissible as a U.S. state. The miniscule attention offered by Congress to the Five Nations’ attempt to enter the Union as the state of Sequoyah—the constitution of which emphasized the distinct sociocultural (if not racial) character of its people— presents strong evidence of this. Indian Territory as an Indian territory did not meet Congressional standards for statehood, just as it had not met its standards for self-rule.706

Legislators were assured, however, that white settlement could mitigate the Five Nations deficiencies; and with that settlement, American government and constitutional rule would necessarily follow. Even American citizenship for Indians in the territory (which came in 1901) was acceptable under these conditions. Congressmen like Vest did not foresee American settlement of the Philippines on the level it occurred in Indian Territory, thus there appeared no route to de-annexation by incorporation.

Congressmen like Orville Platt, on the other hand, did not believe that the United States must rule its “possessions” under the constitution; nor did he think it imperative that every territory under

U.S. dominion have the potential to join the Union. Summing up a long speech before the Senate in 1898, he said:

I think I have shown that the power to acquire new territory is inherent and unlimited; that the right to govern is limited only by the principle and the treaty agreement, upon which alone any obligation to admit as a State can be based, and that these propositions have been sanctioned by the courts since the foundation of the Government.707

Part of his justification for this view was that sovereignty and the right to acquire territory were conterminous, and if the United States were somehow limited in its ability to expand its territory, it would not be fully sovereign. The constitution, Platt insisted, could not curb the United States’ rights as an international sovereign; in that context, the nation had supreme and inherent power. Whether or not that power was subject to international law was another issue; but Platt assumed that those concerns has been settled by the victorious outcome of war with Spain and the Treaty of Paris thereafter. He did, however, discuss at some length the basic right the United States had to acquire title to land by discovery as foundational to its qualification for sovereignty. He quoted from an 1890 Supreme Court decision about U.S. jurisdiction over Navassa Island (a guano deposit in the Caribbean) to make this point: “By the law of nations, recognized by all civilized states, dominion of new territory may be acquired by discovery and occupation as well as by cession and conquest.” 708

Discovery is not often discussed in the contemporary scholarship as part of the jurisprudential effort understand and justify the United States acquisition of insular territories, but as it was fundamental to American understanding of European expansion (and the United States initial heirship to the same), it could not fail to exercise some influence. In 1899, after a long and contentious debate between the expansionist and anti-imperialist factions in the Senate709, anadvance copy of an article written by Carman F. Randolph, which was soon to appear in the Harvard Law review, and would come to be known as one of the five canonical analyses in that publication that set the terms of the debate about American imperial expansion. In this article, Randolph affirms legitimacy of territorial acquisition by discovery under international law, and endorses the view that “the power of expansion is illimitable in point of the law.” On this count constitutional law is an extension of international law, because, he explains “[w]henver the President and Congress join in extending the sovereignty of the United States over a particular territory, their action must be respected by the courts without regard to its location.” This is equivalent to saying the bare fact of territorial acquisition by the sovereign American state is non-justiciable, just as the federal claim of title to preemption to aboriginal land on the North American continent—and, according to Justices like Baldwin in Cherokee Nation, the sovereignty of aboriginal nations—was also non-justiciable. 710

Randolph does not believe, however, that this international legal right to acquire territory necessarily implies the constitutional right to hold it without the intention of admitting it, eventually, into the Union. Along these lines be speculated: “There are in the United States ‘citizens.’ ‘wards’ (Indians), and ‘aliens’…[i]s there room for ‘subjects’ who will be burdened with duties without enjoying the compensatory rights?”711 “Wardship” as it applies to aboriginal Americans appears now in the legal lexicon as a defined an accepted term of art.712 The fact that the category has historically been developed as an outgrowth of the doctrine of discovery was not something that Randolph explored; nor did he question how it might apply in the Philippines, despite the fact that he saw the distinct possibility that some populations on the archipelago may require being governed by the United States as “wards.” He suspected this may come to pass even if the U.S. rule proceeded constitutionally and incorporated the Philippines with the goal of eventual statehood. But the classification of some Filipino “dependent nations” or “tribal Indians” must not he “arbitrary,” he warned, “for the constitutionality of our discrimination against the Indian is based on the fact that he owes allegiance to a political other than though inferior to the United States.” Thus Indian policy could only be exported to the those Filipinos who had not been under Spanish jurisdiction at the time of American conquest, but had instead “been governed by their tribal organizations.” 713

As we’ve discussed at length above, the constitutional justification for subjection to wardship was a matter of perennial debate. And yet, the assumption that Indian sovereignties were subservient to the United States did find a constant support in the doctrine of discovery as the Marshal court promulgated it. By Randolph’s reasoning, “tribal” peoples in the Philippines who had never been conquered nor paid allegiance to Spain (and they did exist—the Muslim Moro polities on the southern island of Mindanao, among others, for the most part remained unyoked to the Spanish Empire) would have presumably still borne the burden of having been “discovered,” and with it whatever international jurisprudential impact that discovery made on their sovereignty and land title rights. He did not, however, explore the implications of this in this essay.

Another of the legal scholars to treat the subject of U.S. colonial rule in the Harvard Law Review was James Bradley Thayer.714 Thayer’s analysis was much more favorable to U.S. imperialism; and his argument discussed U.S.-Indian policy in that context at greater length. Beyond his positive view on the legality of the United States annexation of foreign territory, he voiced the messianic Americanism that would run contrapuntal to “Manifest Destiny” in the twentieth century: “’Let not America forget her precedence of teaching nations how to live.’” That “precedence,” according to Thayer, translated into “governing of Cube for a considerable time, if not forever, and [the possession] of Puerto Rico and more or less of the Philippine archipelago, with the duty of furnishing a government for them.”715 This national duty emanated from the power in inherent in the United States as a sovereign nation—a power that it held anterior to the constitutional formation of its government.716 The power of acquiring colonies, Thayer continued, was “incident to the function” national sovereignty. The power to hold those colonies followed from the power to acquire. And, incident to the power to hold territory, was Congress’s right to “to determine what the political relation of the new people should be,” with or without their consent. Thayer offers U.S.-Indian relations as a well-established example of the American sovereign exercising its colonial power as sovereign. This relation, he explained, was one where the Indian nations were treated as “separate people,” left to their own internal government, with the federal government given the broad constitutional right to govern their commerce. But Congress also had the power— as a sovereign—change that political, and to subject Indian polities to any form of government it wished. Thayer claimed that Congress had not yet “by any wholesale provision, undertaken to bring [Indian polities] under subjection to [United States] [but] that congress might do this at any time, is settled.”717

Thayer then goes on, remarkably, to settle the entire question of the United States’ right to acquire and rule territory with reference to Taney’s Rogers opinion concerning U.S. jurisdiction in the Cherokee Nation.718 And the portion of this decision he quotes bears directly on U.S.-Indian relations as constructed by the doctrine of discovery. Thayer, however, elides the mention of discovery, and reproduces Taney’s opinion as if it merely affirmed Congress’s inherent right to exercise jurisdiction over Indian nations. Taney, however, was attributing that power directly to the preemption of aboriginal title the United State government asserted under the doctrine of discovery. Why Thayer—a careful legal scholar by all accounts—would fail to provide this context is uncertain. But the omission does have the effect of rooting Congressional plenary power exclusively in Congress, not is some archaic and dubious principal of customary international law. Whatever the case may be, Thayer proceeds to quote Taney’s assertion “we think it too clearly established to admit of dispute that the Indian tribes residing in the territorial limits of the United States are subject to their authority,” as sufficient to establish “as settled, that it is for Congress or the treaty-making power to say what shall be the permanent political position of a new people.”719

While being careful not to suggest a teleological relation between U.S.-Indian policy (or, in particular, U.S.-Cherokee relations, as those foundational were to the latter), it is clear that the jurisprudential parameters of U.S. extraterritorial imperial expansion, and colonial relations with extraterritorial possession, had a strong genealogical link to American colonial-imperial subjugation to aboriginal polities in North America. This is evident, if nowhere else, in the conceptual refinement of plenary Congressional power in the U.S. Supreme Court over the course of the nineteenth century. But what is often veiled in the discussion of plenary power in general is its specific evolution out of pre-constitutional title claim, via the doctrine of discovery, to the very ground on which America came to stand. As such, the self-appointed American title right over aboriginal occupancy right sat at the nexus of positive and natural law.

This tension of laws inherent in the American primal scene was one between constitutive and constituted claims to sovereignty, that is to say between pre-judicial power of a sovereign, as it were, in a state of nature, and constitutionally justiciable claims grounded positive law. In establishing—through the Johnson decision—its territorial claim to aboriginal land, and by announcing, with the Monroe Doctrine, its pretension to hemispheric predominance, the United States both internalized constitutive aspects of the European jus gentium by claiming pre-constitutional powers inherent in sovereignty, while simultaneously exceeding those powers by projecting them beyond state borders.

The Doctrine of Discovery innovated by the Marshall court was an act of positive, constituted, jurisprudence that preserved, as a kind of moral remuneration, a trace of “constitutive” natural law right through “occupancy title.” Marshall relied on the fragile and contested Doctrine of Discovery itself as principle of positive international law to invest the American state’s preemptive title to indigenous land. But this was not sufficient of ratify U.S territorial sovereignty. As Marshall acknowledged, Discovery functioned only as a tacit contract between European and American sovereigns, and could not be expected to enjoin Indian Nations by itself. To do that, he needed residual natural law ideas—abstract, and pre-judicial—to both invest indigenous polities with a moral claim to abridged territorial sovereignty (occupancy title), and at the same time deny them full, unencumbered perfection of that title due to a presumed incapacity of indigenous polities to participate in realm of sovereignty proper. This move acknowledged a natural right to territory while at the same time ensuring that natural rights would ultimately be subsumed by higher order positive legal apparatus of Euro-American states, despite the fact that Euro-American states also ultimately located their sovereign territorial integrity in pre-judicial, constitutive, natural rights.

It is also important to remember, insofar as discovery operated in European expansion, it did so as colonial appurtenance to established state/crown jurisprudence rooted in metropolitan territorial sovereignty. European sovereigns justified their empire through discovery, they did not need it ratify their territorial sovereignty in Europe. Discovery, however, in the hands of the U.S. Supreme Court, became sine qua non of the American territorial state. By that understanding alone, the United States based its sovereign legitimacy on the domestic constitutive, pre-judicial use of a precept customary, justiciable international law.

It cannot be forgotten, however, that the discovery doctrine in the American context was also predicated on race and civilizational capacity. Occupancy title was an index of racial/civilizational inferiority and the presumed incapacity of aboriginal societies to form Euro-American-style territorial states. This racial component adds yet another stratum to the constitutive law on which the United States founded its title right to North America. Thayer makes no direct mention of race as it relates to the capacity to govern in his essay;720and yet his reliance on Taney and the history of U.S.-federal relations in considering the U.S. role in the Philippines made racial prejudice implicit. A third Harvard Law Review writer on U.S. colonialism, however, made race the centerpiece of his argument for territorial acquisition; and it was his work that would have the most significant impact on the Supreme Court decisions that would soon codify the terms U.S. twentieth-century colonial empire.

Abbot Lawrence Lowell’s article for the Harvard Law Review suggested a third optic by which to view the current question of U.S. extraterritorial empire.721 With a survey of constitutional law and judicial precedent (one that seemed to almost scrupulously avoid any consideration cases involving American Indians), Lowell sowed that seed of what would flower in the Supreme Court two years later as “the incorporation” doctrine. In a nutshell, this doctrine proposed that the United States in some cases acquired territory with the express intent of making it a state, in which case Congress extended the constitution to that territory by treaty or statute, thus incorporating it; but in other cases, it annexed territory without that intent, and held it as an unincorporated appendage. Lowell did not divulge the metric by which that distinction was to be drawn in the Harvard Law Review; but two additional pieces he authored drew an austere color line.

In an 1899 Atlantic Monthly article, Lowell argued that, contrary to popular opinion, “colonization” had always been integral to making of the American public. What else, he asked, did one call U.S. westward expansion across the continent? He went on to discuss the multifarious way the United States had prosecuted its colonialism over the years: by purchase (Louisiana), by voluntary annexations (Texas); and by conquest (Mexican North America). This discussion, however, completely erased aboriginal polities from the picture. Lowell talked of the “vast regions of North American uninhabited by civilized man” over which “our fathers…plant[ed] an ever extended series of new communities” as if they were in fact terra nullus, as if the aboriginal inhabitants were more akin to wildlife than human beings. This genocide by amnesia notwithstanding, Lowell maintained that as the United States expanded its empire extraterritorially, it would confront problems that it did not in North America—namely that white men would be, at least initially, in short supply. Full political rights for these territories should be withheld, he insisted, because “the popular belief that all men are fitted to govern themselves…could [not] be further from the truth.”722

Lowell did not contest that all races are due “natural rights” (he seemed to agree with Beveridge that these were reducible to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”) under U.S. colonial law, but other rights that male U.S. citizens enjoy— suffrage, for example—fell into a civic realm in which certain races did not have the capacity to participate. Indians, for example, were “quietly assumed that so long as they remain in their tribal state they [were] not men” (presumably, Lowell meant “men” here to define those with minimum level of civic “capacity”). And as far as Filipinos were concerned, “to let [them] rule themselves would be sheer cruelty both to them and to the white men at Manila.” 723 Lowell expounded this view further in a paper the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, saying that “the Philippines are utterly incapable of ruling themselves in any civilized way, so that there need be no question about the need of obtaining the consent of the governed, to distract us in our pursuit of their welfare.” In Puerto Rico, however, because the population “although foreigners, are largely of European blood,” “the political aspirations of the people cannot be disregarded.”724

Lowell’s rhetoric of governing capacity, race, and the relationship of the United States to its colonial possessions would have an impact on the Supreme Court’s assessment of extraterritorial empire, and to the policy that Congress would come to enact as a colonial government. But while U.S.-Indian relations formed aspect of the backdrop to his ideas, he did not consider them, in their political relationship with the United States, as a significant part of U.S. colonial empire. A close colleague of his at Harvard, Albert Bushnell Hart, did, however, “analyze the existing system of hierarchical rule in and outside of [U.S.] continental boundaries,” concurring with Lowell that in another national setting U.S. system would be deemed self-evidently “colonial.”725 Hart—whose influence extended to President Theodore Roosevelt and Secretary of War Elihu Root—made the observation that Indian Territory was the “most perplexing of Brother Jonathan’s colonial experiments.” He went on to enumerate the “intolerable conditions” under the Five Nations government (according, he says, to “Mr. Dawes”), and claim that they “may suggest the need of wisdom in organizing colonies overseas.” Hart was one of the only individuals commenting on the subject to see the parallels between the United States administration of the Five Nations (and the Cherokee in particular) and European forms of colonialism. He cited the particular resemblance of the political situation in Indian Territory to that of the Native Princely States of India—aboriginal sovereignty princedoms that treated with the Raj, and, like the Five Nations, maintained a level of internal political autonomy under an imperial system of government.726

Hart wrote this assessment in 1901, and clearly believed that Indian Territory at that time figured as part of the American colonial archipelago. In fact, he evaluated the state of U.S.-Five Nations colonial relations as a contemporary problem, part and parcel of what the United States was just beginning to face with its new insular “dependencies.” Hart portrayed Indian Territory as a cautionary tale for further American imperial endeavors; and yet also an ongoing and structurally significant aspect of the early-twentieth-century imperial moment. Unlike so many scholars that came after him, he understood that the emergence of “extraterritorial” imperialism in America did not neatly punctuate the “territorial” phase. But just as with the Cherokee nation three-quarters of a century earlier, it would be up to the Supreme Court to impose the hazy border where the American state ended and its empire began.